Liner supercycle is fading

Liner supercycle is fading

Container sector stakeholders have benefitted substantially from the extended container supercycle, but do they face tangible risks in the short-to-mid-terms?

Back in March 2020, few (if any) container industry stakeholders could have expected liner operator profitability to surge (and remain on that trajectory) to the extent it has over the ensuing two years. Developments in the container sector were largely counter-intuitive for 2020, and trends on both the revenue and profit fronts have continued to exceed previous records of performance on a sustained quarterly basis since mid-2020.

The drivers are well documented – a heady combination of cargo growth, supply chain and port congestion issues, pandemic-related shutdowns, and demand rapidly outstripping capacity. The flip side of course is that shippers were and remain frustrated and are paying ever increasing amounts for freight. Ultimately, a sector that was characterised by its leading players rarely being able to maintain profitability year-on-year, has been transformed, with the protagonists adopting new strategies aimed at revenue model and profitability enhancements (albeit aided by the extremely positive market fundamentals). All have embarked on strategic growth and expansion programmes since mid-2020, many funded by cash and equity holdings, rather than bank financing. In addition, the strategic commercial driver for many has become profitability, rather than gaining market share. A few (noticeably the Maersk, MSC and CMA CGM groups) have significantly ventured into logistics territory and are busily re-inventing themselves as end-to-end supply chain companies.

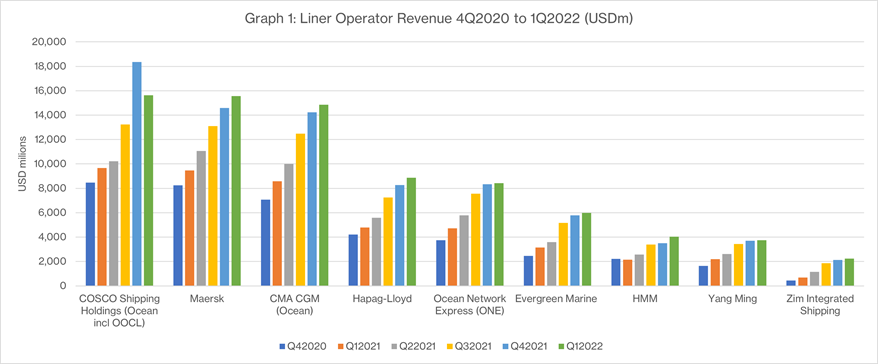

A brief review of the revenue booked by leading global liner operators highlights the significant and sustained growth seen since mid-2020, by which time the world had emerged from national lockdown periods, and manufacturing output and demand growth had returned (fuelled by the digital commerce boom). Total revenue figures are very different per company, given the respective sizes of fleets, trade route focus, cargo mix and differentiation between spot and long-term contract business, but in all cases, revenue has grown steadily over the six quarterly periods under review here. In fact, in virtually all cases, revenue has at least doubled over that timeframe, and this of course has no direct relationship to the number of TEU carried (graph 1). Well-documented analyses in the press have highlighted that current average short-term spot freight rates in the key Asia to North Europe and Asia to US West Coast trades are about three to four times the levels of mid-2020 (when the markets started to significantly improve).

White-hot Profitability

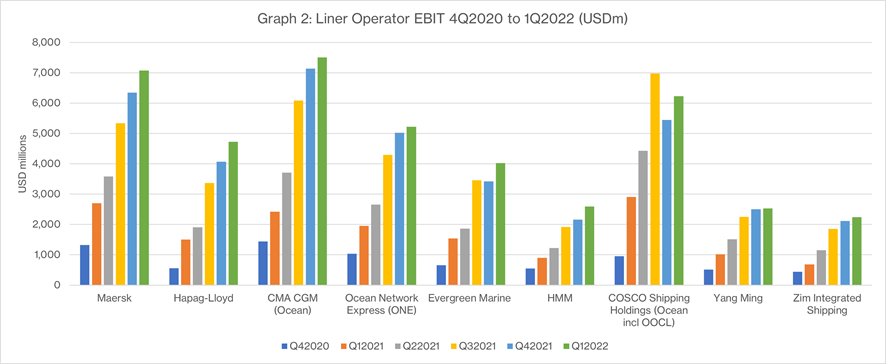

The market developments outlined above have all translated into record profitability for liner operators, with graph 2 highlighting the exponential growth in quarterly EBIT for some of the major players. The only major notable exception here is the 1Q 2022 decline shown by COSCO Shipping Holdings (relating to COSCO and OOCL’s performance) and is attributed to a much steeper decline in volumes compared to peers, which is more pronounced due to COSCO and OOCL’s emphasis on the domestic market that was affected by further pandemic shutdowns. A key measure of performance here is that in early 2020, quarterly operating profit margin (per company) may have been at around 5% or below, but by late 2020, this had moved into double-digit territory, and just kept rising. For example, in 1Q 2022, HMM recorded a 64.2% operating profit margin, with Hapag-Lloyd booking 53.3%. It is also worth noting that in 1Q 2022, the total EBIT recorded by nine of the largest market players (excluding MSC) was in the region of USD 42bn.

Cash is King

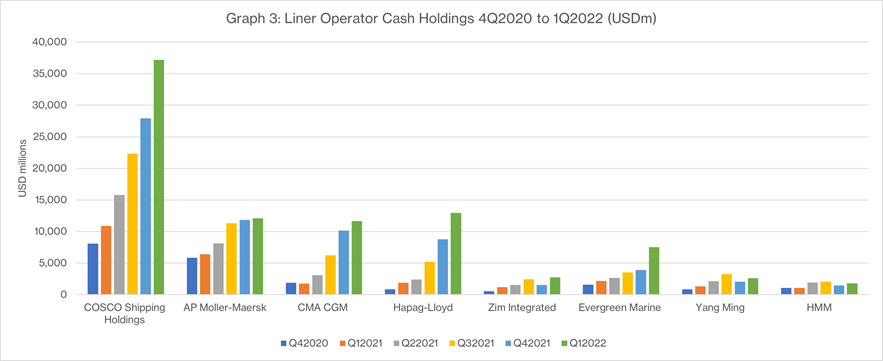

Turning to a balance sheet perspective, the liquidity of liner operators has substantially improved during the late 2020 and early 2022 period (graph 3). COSCO Shipping Holdings, AP Moller Maersk (as parents of their respective liner operating entities, for which figures are not recorded), CMA CGM and Hapag-Lloyd, all showed cash holdings in excess of USD 10bn at the end of 1Q 2022, contributing to significant working capital surpluses. This huge liquidity boost has allowed companies to rapidly expand, enabling corporate acquisitions and in some cases, providing for initial down payments on commissioned newbuildings, and secondhand acquisitions alike, while also allowing for interest-bearing loans to be paid down and bond obligations met.

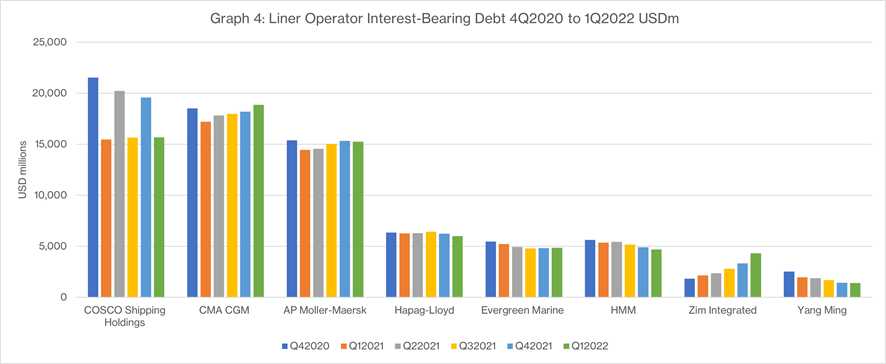

Indeed, what may have been seen during other cycles as a worrying increase in debt related to the commissioning of newbuildings and corporate acquisitions, is apparently not curtailing the availability of financing. While some companies still have significant interest-bearing debt (USD 18.9bn and USD 15.7bn in the cases of CMA CGM and COSCO Shipping Holdings respectively at the end of 1Q 2022), the debt totals have in most cases not grown significantly during the last 18 months (see graph 4). Given the sizeable capex commitments of the major players, many have not only met repayment obligations, but total interest-bearing debt has largely trended downwards.

The one exception is probably Zim Integrated Shipping; in early 2020, the company was in an unprofitable and highly geared position, but by the end of 1Q 2022 it had recovered to stand as a financially sound business. Over the same time frame, however, its interest-bearing debt more than doubled, growing from about USD 1.8bn to USD 4.3bn (largely on the back of huge fleet expansion). Admittedly, the company is in a far better position to repay debt, but the escalation and present leverage position is noteworthy.

So, as it stands, does the liner sector continue to operate in a supercycle? Will the leading players continue to reap the benefits of record-high freight rates? Are there material risks to the current status quo?

While we feel it is very unlikely that the leading players will experience any material changes to their positive financials in the next six to nine months, more significant risks for the medium-term must be considered.

Container market warning signals

Short-term

- There have been real signs of a decline in cargo growth during 2Q 2022 compounded by the factory shutdowns and port congestions in China as well as normal seasonality. Current estimates of global cargo growth for 2022 range from about zero to 2% to 3% (down from 6% in 2021), with Maersk management now more negative about future growth

- Average spot freight rates on the core Asia to North Europe trade have declined by about 20% to 30% since early December 2021 (and by about 10% on the headhaul transpacific route); however, these remain at record-high levels when compared to early 2020. There is likely to be a correction or “normalisation” of freight rates in the next six months, however, the degree and rate of any of rate decline is a genuine unknown, and the consensus is that rates will remain well above OPEX on individual trade routes.

Medium-term

- Along with freight rates, charter hire has risen significantly in the last 18 months. Liner operators can afford the extra costs of course, but some have insulated themselves to a degree by focusing more on their owned fleets. Companies that are more highly exposed to charters (at record-high rates) for the next three to five years (and this also includes Zim Integrated Shipping) will need to carefully manage operating costs.

- Bunker costs have significantly increased (average VLSFO prices at Rotterdam were about USD 290 per tonne in mid-2020, compared to the current level of USD 880 per tonne) as oil prices rose with pandemic lockdown disruption easing, and now in the midst of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine. The leading players have greater exposure to this volatility as their fleets have increased in size. For example, AP Moller Maersk spent USD 3.84bn on bunkers in 2020, but this increased by 40% year-on-year to USD 5.37bn in 2021. Feedback we have received from suppliers indicates that the credit lines they extend to the major liner operators have increased during this time.

- The size of the current container vessel orderbook (currently standing at about 6.8m TEU/910 vessels) is also weighted towards larger ships (of at least 8,000 TEU) and for deliveries in 2023 and 2024. Firstly, very sizeable outstanding debt needs to be serviced, and the newbuildings delivered (at a rapid pace) from early 2023 onwards will bring a rebalancing of supply/demand fundamentals at the trade route level. Supply chain and congestion issues may be in evidence, but there is the very clear sign that there could be potential overcapacity and cascading concerns that will alter the supply/demand balance as larger ships are re-deployed to smaller trade lanes. Ultimately, as history has shown us, freight rate erosion for liner operators remains a genuine threat. While some newbuilding vessels may replace older vessels, the jury is out on the level of scrapping likely to materialise given the importance of even elderly tonnage to owners and their present earnings potential.

- Only time will tell if the diversification into logistics territory by some leading liner operators is a success.

- The evident profitability and freight rates on offer have attracted new entrants into the deep-sea container shipping markets since mid-2021. These include Ellerman City Liners, Transfar Shipping and Rif Line. In addition, several regional liner operators (SM Lines, TS Lines, Sea Lead Shipping and China United Lines) have significantly extended their services beyond intra-Asia (primarily to the transpacific trades). All of these companies will see increasing operating costs (for charter hire and bunkers) and will be extending credit lines with suppliers. As with previous historical supercycles, there is uncertainty regarding either their longer-term prospects (or survival) and current network profiles when the market “normalises”.

Questions regarding fuel technology

There is a consensus amongst many industry commentators that the largest question mark for the container sector is the eventual true impact (cost) of the decarbonisation process towards a net carbon zero goal for shipping. Some liner operating groups (including Maersk and CMA CGM) have been more proactive in terms of guiding or influencing the sector towards certain types of ship technology and green fuels (including methane and LNG), however, others remain undecided and have instead opted to retrofit ships with scrubber technology and buy lower-priced IFO 380 fuel. This is not a viable long-term objective and the ultimate cost of the transfer to the new fuel era is unknown. Should individual companies need to re-align strategy or delay commitment through indecision they may well have to play a significant catch up in terms of costs.

Ultimately, the heightened fundamentals of the liner sector are not sustainable for the long-term and when the current supply chain issues become less prominent, prudence will be the watchword.

Read more of our Infospectrum Insights here!